It is common in public institutions, art galleries, museums and libraries that the acquisitions departments have to buy certain works or items. As a private collector the focus of the acquisitions is 100% personal, will it be matchboxes or … books by artists?

As a book artist I think of my relationship with books as introverted and exploratory, a maze to be negotiated between what is in my head and what can be put down onto paper. As a collector my relationship with books is almost the opposite, open and inquiring. But the maker of books and the collector of books are not blind to each other—my own work and exploration with the book, as well as my interests in subject matter and current thinking about the book all play an important role and influence my collecting decisions. I collect what resonates for me, what I’m intrigued by, but also, particularly with historical works, those books that I believe are important.

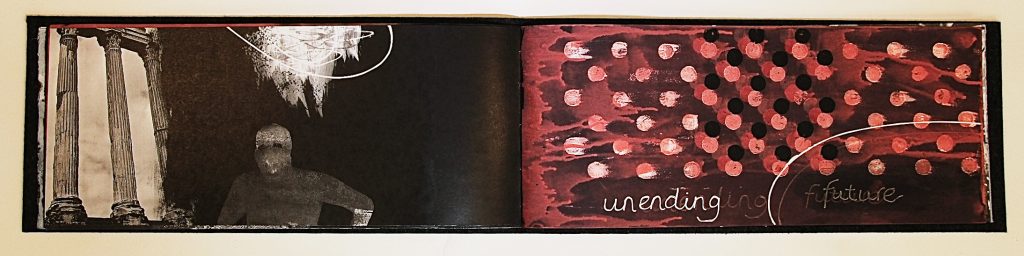

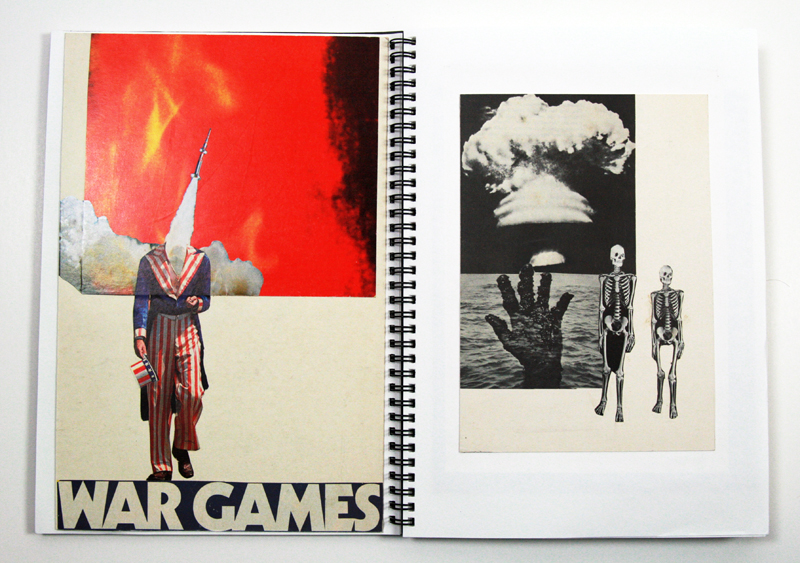

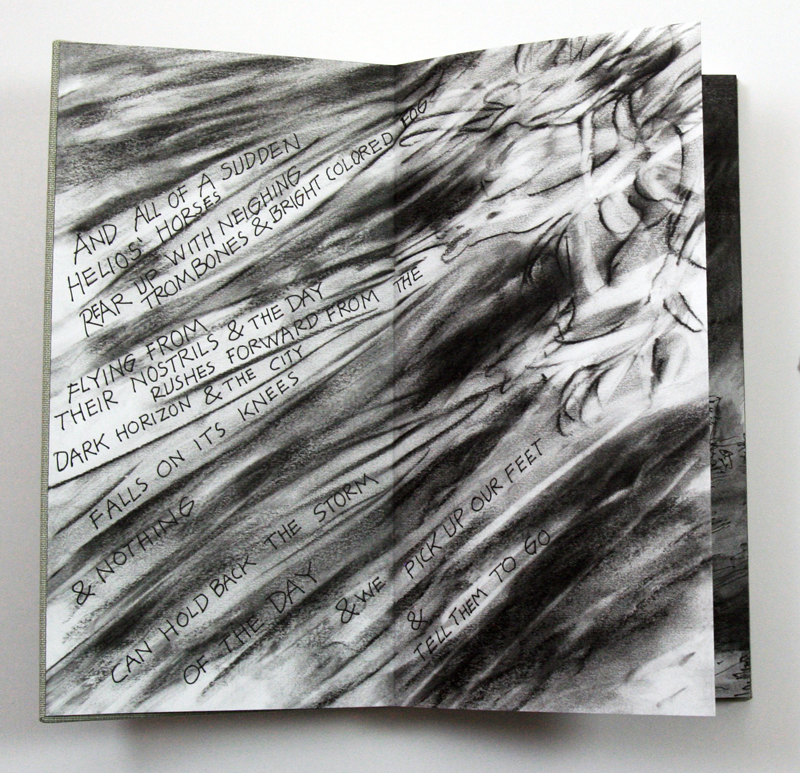

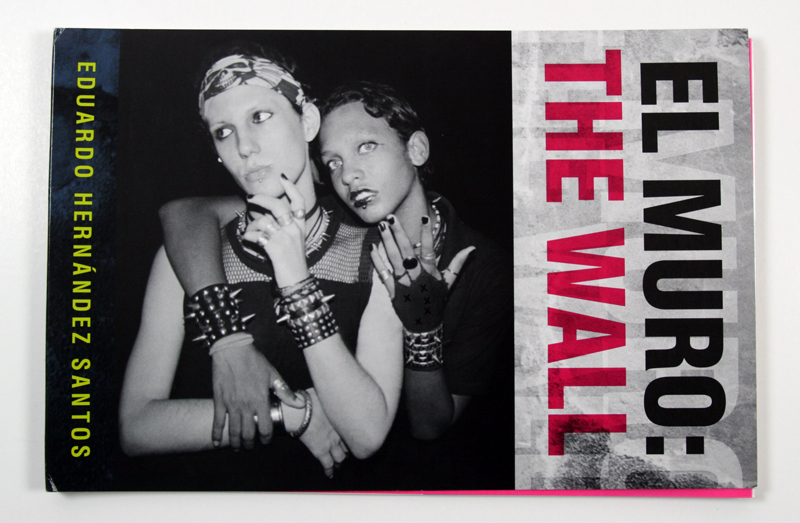

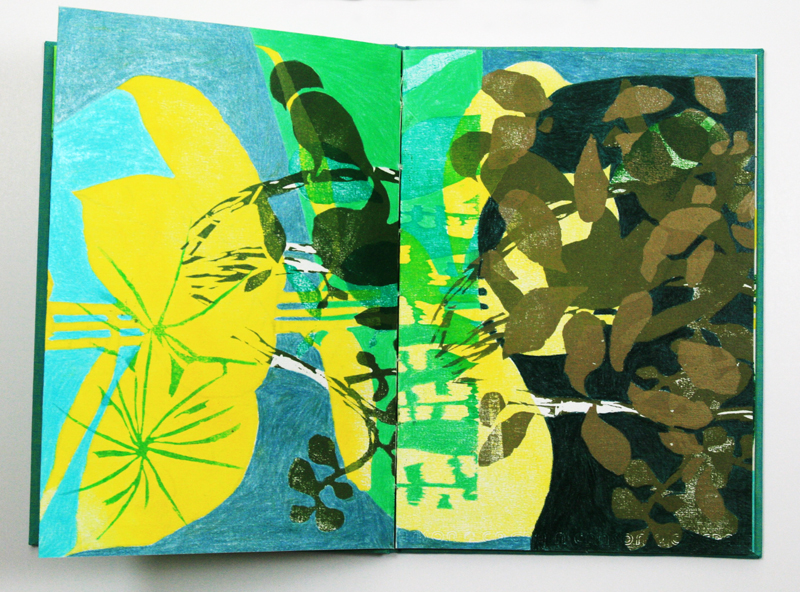

Primarily, it is the subject matter that gets my attention. There are themes that I’m interested in: the exploration of the environment, natural and built; the book as a political and social platform, giving voice to alternative points of view, recording social and political change; the book as diary, a personal space for storytelling, for expressing a specific point of view; also the book stripped of words, as visual narrative, narrated by the painted mark, the printed mark, the photograph, the drawn line, plus the collage/montage of painted mark, printed mark, stitched line, photograph, drawn line in any and every imaginable combination…

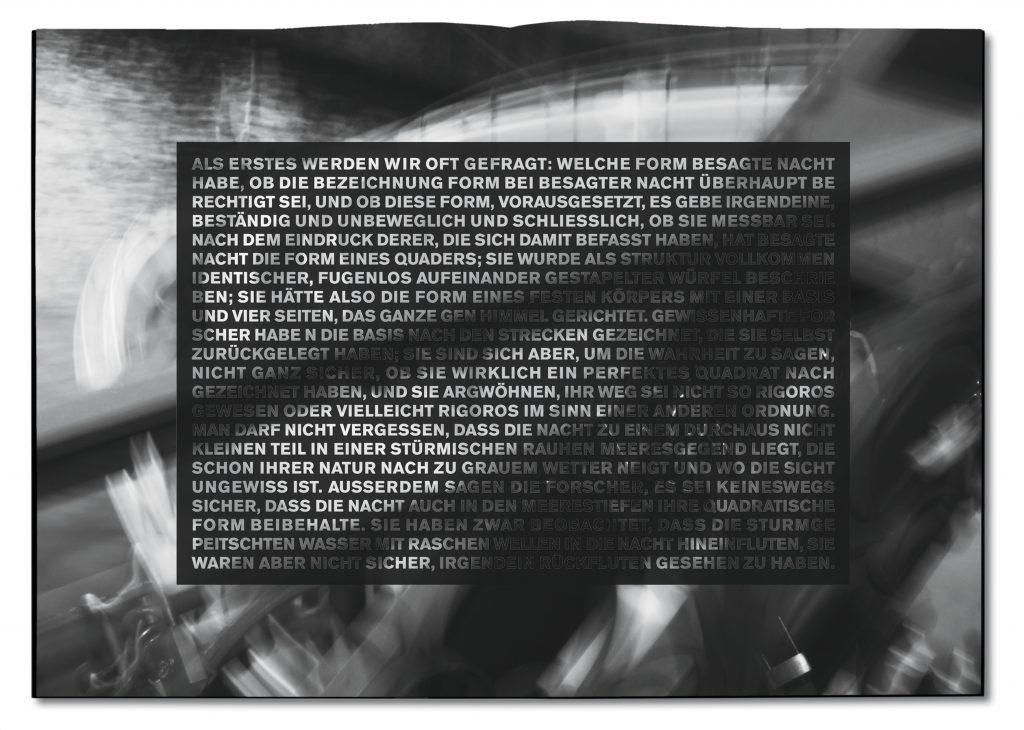

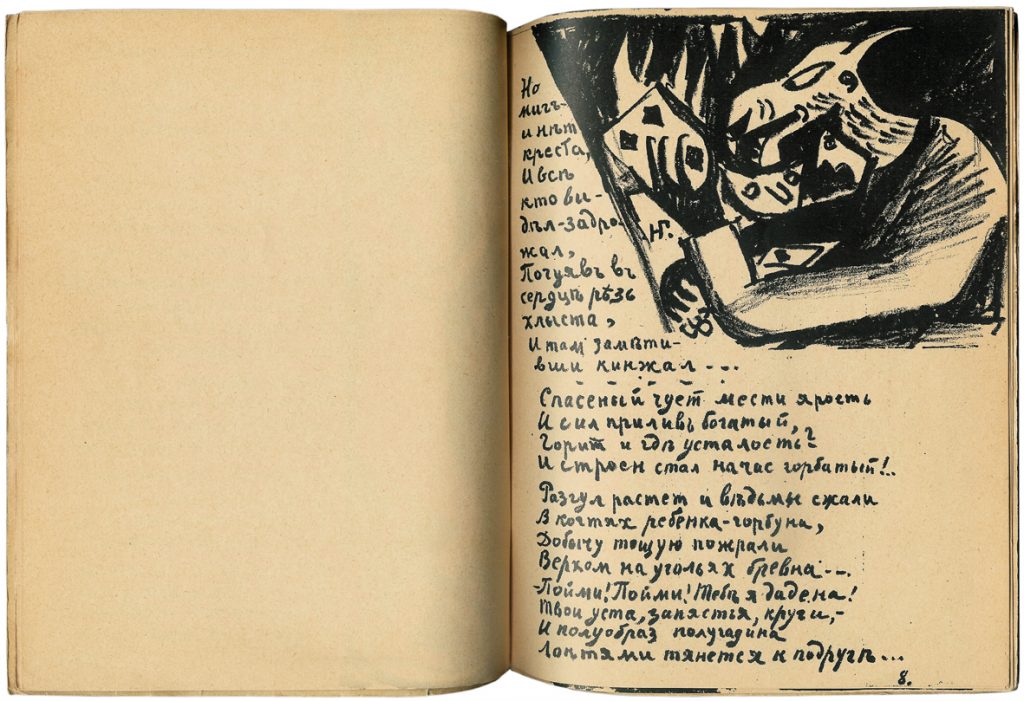

All books are an expression of being human. Being human—that touches all art (and beyond) and is what connects me to a book. As well as connecting to the subject matter, the bookwork can connect me to the maker. I like to sense the movement, the thinking, the process of production, the artist working within the book. I like to come across the artist’s fingerprints so to speak. This is what differentiates books by artists, even those that are ‘commercially’ produced, from common commercial publications. If I take down a copy of Tree of Man by Patrick White or Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak and hold it in my hands and flick through the pages, I don’t sense the author in the book object itself or even in the book’s design, the individuality of the author appears only in the actual text. In books by artists, the artist is present in the object itself.

Beyond subject matter, the book as performance piece: every book in the process of being read, the slow, rhythmic motion of the pages being turned, could be considered to be a performance, not an extroverted show à la Gilbert and George but a private performance that requires no audience. Books that revel in the awareness of this motion, that draw our attention to it and make us realise our complicity are powerful works, enhanced by a four dimensionality, time passing marked by action, which otherwise goes unnoticed.

Beyond subject matter, the book as space for text, for image, for image and text: this applies to all books, the interplay of text and image. The degree to which the artist is aware of their freedom to put text where they want, to use image how they want, is obvious immediately in a work. The standardization of book formats has been set deep into our subconscious because it is and has been used repeatedly for so long—that it is normal and being normal, means we are blind to it. But if the artist breaks the norm frivolously, it looks bad. If the artist breaks the norm knowingly the work, the text, the image has new power.

Does the collector have a responsibility? What about the canon?

“Ja, das ist schon ganz schön, aber hier ist es nicht ganz konsequent, oder?” 1 I like this comment. It translates, “Yes, sure this is all very nice but it’s not so significant, is it?” How many works, not just books, could have this comment tagged onto them? Many indeed. But how does a work qualify as “significant”?

In her piece, Critical Issues / Exemplary Works, Johanna Drucker lists ten criteria2 that she and a colleague developed for assessing artists’ books submitted to the special collection of a public library. If a book fitted the criteria, it was purchased, and I guess we could say, it was significant. The list of criteria, which she states “are simple”, is a tough list and I sense that most books would fail on one or several criteria and some on all of them. Needless to say, Do I like it? was not one of the criteria. I’m not poking fun at Drucker. I agree with her claim that “the field of artists’ books suffers from being under-theorized, under-historicized, under-studied and under-discussed,”3 but key to being a private collector is liking the work you are buying. Liking doesn’t have to be a superficial response. Liking can be an informed response, particularly if you have seen hundreds of books.

Another purpose for this list of criteria could be to aid the creation of those “fundamental parameters”4 and the building of a canon of artists’ books, book artists. Although I can see a purpose of the artistic and literary canons, I am also suspicious because, so often, and perhaps it cannot be avoided, they are or have been formed within broader social and cultural parameters that are intrinsically exclusive. If a canon of artists’ books is to be established it will happen through critical discourse over time—the key works will continue to resonate into the future and also those in the future, will reach back to the works that resonate for them. The role of collectors, to what degree they actively participate in the critical discourse, the building of a canon, like everything to do with collecting, is a personal choice, but ultimately their most important role will be in buying books because, if the books are bought, the artists will (probably) continue to make them.

Endnote

Finally an endnote that’s not final—back to history. There are those who claim that artists’ books appeared in the 1960s, and perhaps they did, but I like to look wider. I think it is necessary to know what and how artists worked with the book in the past. After all, artists have been involved with the book since the beginning. The degree to which they were just workers being directed or have had more of a hand in directing fluctuates across the centuries and, yes, there comes a point were the balance tips and the artist has actual control. Regardless of where the line is drawn, books from the past are our cultural memory. Engaging with them, studying them, knowing them, is an acknowledgement that our books didn’t arrive with today’s newspaper, that the books we are producing today exist in a cultural and historical context.

1 Kaspar Mühlemann, Swiss typographer, quoted by Ulrike Stoltz, USUS, personal communication

2 p. 4, Drucker, Johanna Critical Issues / Exemplary Works, The Bonefolder, vol. 1 No. 2, Spring 2005

3 p. 3, ibid

4 Drucker, Johanna, Critical Necessities, JAB 4., Fall, 1995 p. 1.