The beginning of my collection was my own work. I began to collect the work of other artists out of a need to connect with artists who were working with books. By the time I had more than 20 books I knew I could no longer keep them wrapped in paper in a couple of drawers in the plan chest in my work room. However the impetus towards formalising the collection happened with a first visitor coming.

“These books,” he said, indicating to the limited edition books, “are all very nice but they are not very democratic, are they?” I hadn’t heard the word ‘democratic’ used in this way. When questioned, he replied, “Well, almost no one can afford them and no one gets to see them.” Straightaway I felt ready to rise to the challenge. I could open the collection to the public by appointment and allow a bit of ‘democracy’ to touch these undemocratic books. It would take a catalogue and a website.

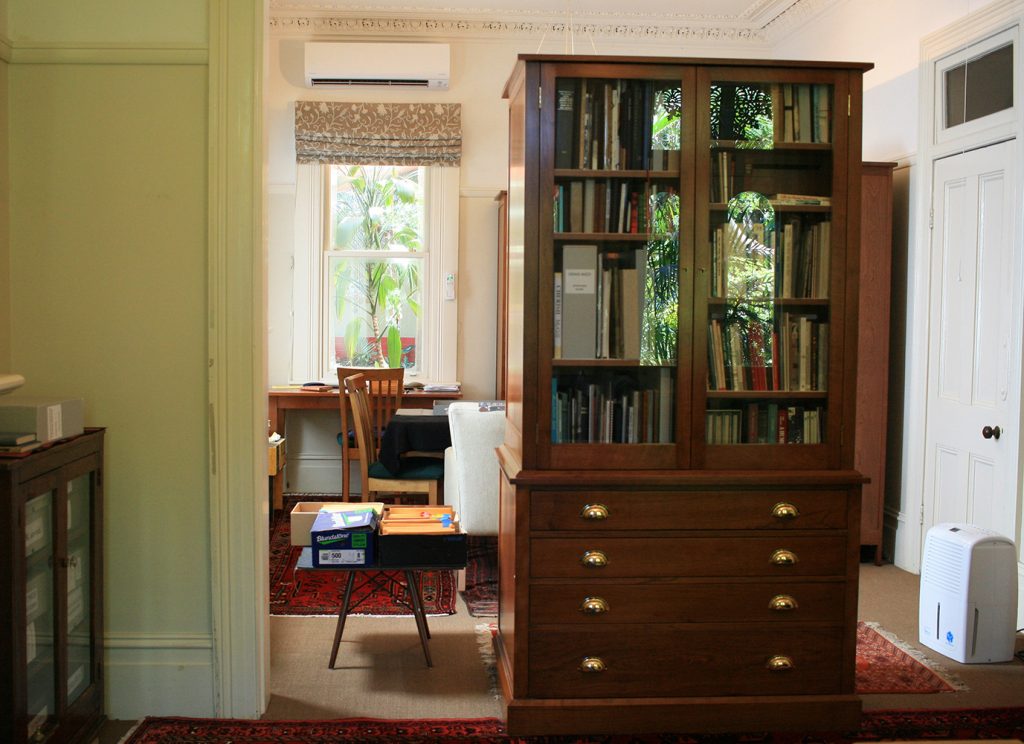

The collection is kept in a double room, formally the living room of my 2-storey terrace. Due to the age of the house and its Victorian era closed design, the room can be shut off and all traffic clatters by outside along the corridor. The room is dehumidified. The relative humidity in Sydney is rarely lower than 60% for more than a few days. Through a wet summer it can sit above 80% for weeks. In spite of all possible insurance, by far the biggest risk to the books is dampness. The relative humidity in the room is maintained at about 45–55%, the temperature at around 22-26°C in Summer.

The books are shelved in custom-built cabinets with doors to reduce dust and insect penetration. Many books are in boxes. Some books must have boxes, for their protection and the protection of the books around them, for example, Richard Long’s Papers of River Muds that comes in a slipcase covered with one of the mud papers, which is like sand paper. Ideally every book should be in a box but then I would have to spend all my spare time making boxes.

The cabinets have been custom built because no standard shelving unit is designed to hold large folio size books and because we are dealing with the work of artists, this size occurs more often than the commercial publication average. At the other end of the scale are the miniature books, which have their own box, like a shoebox, with ‘file sleeves’ alphabetically arranged each containing the work of a particular artist. Then, of course, there is every size in between.

There are two shelving challenges, the first, dealing with the huge variation in the sizes of the books and the second, keeping track of the books, being able to find them when I want them. I move books, change their shelf and/or cabinet, as seldom as possible. A major move means a relearning, and an updating of the catalogue both digital and paper, so usually it happens only when a new cabinet arrives. As much as possible, I try to keep the books which are connected together, say historical books, or books by a particular artist. It is seldom that all the books by a particular artist can be kept together, artists are notoriously good at making books of any size. Also a book in which three artists have collaborated can’t be kept in three different places.

At the same time there is a need to use the space efficiently. “The book is a physical object and for efficient storage that is the only quality you have to consider.”1 Shelving books only according to size would increase the efficient use of the space, and, as with any growing collection, space and the increasing need for space is an ongoing issue, but grouping books according to subject or artist, if possible, helps with remembering where they are. Friend and fellow collector, Jack Ginsberg told me that at some public libraries, books are stored in stack according to the their size only. A book arrives and it is placed on the shelf where it best fits. It is given a placement number or code and there it remains. The mind boggles at the possible sequences of books that could occur, all determined by the arrival of the post. Well, it’s probably not that fickle, but I can’t imagine trying to keep track of books in such a haphazard, yet physically ordered system.

Cataloguing: a way of remembering, permission to forget

By the time I had 20 plus books I knew I had to keep track of them in a system outside my head. I needed a catalogue and a cataloguing system. I have learnt on the job. Every book is catalogued from the smallest to the largest.

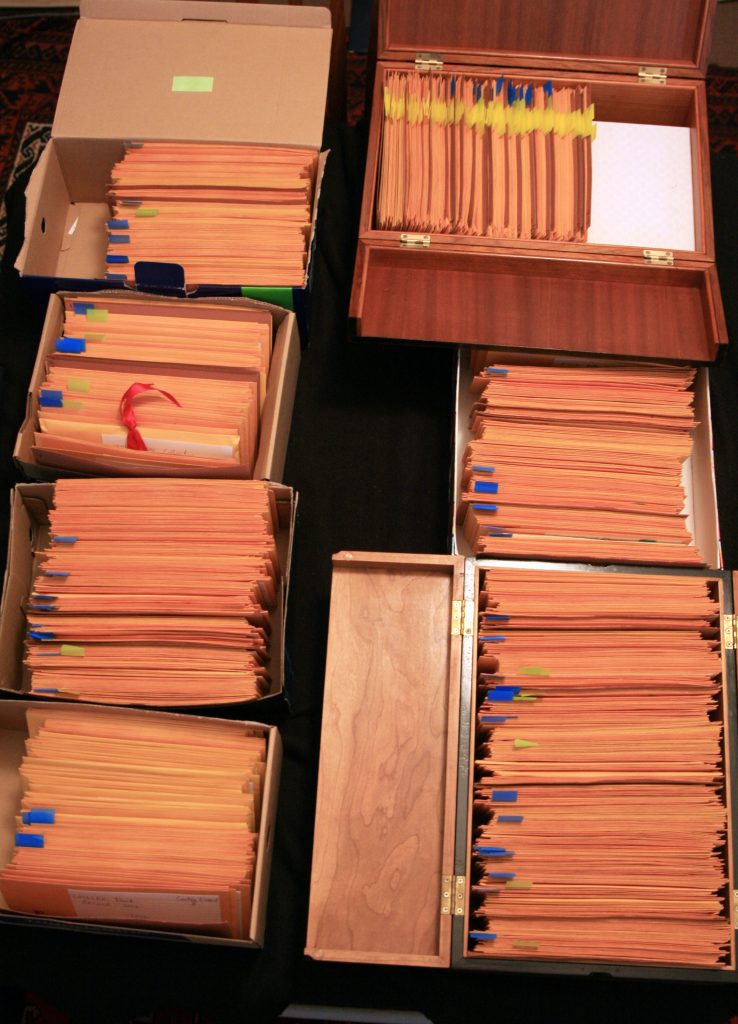

The core catalogue had to be a card catalogue. Some visitors have been baffled and amused by this decision because they think that having a computer based system, a spreadsheet, must be quicker and more efficient. I have discovered that this is true and false. Ideologically, I was committed to having a system, which, like the book itself, was entirely free of computers and electricity. I believe the book’s survival into the future will be this independence from electricity—after all, books were around long before the electric age, but we tend to forget this. In the world of the book the power socket is irrelevant.

Every book is given a reference number. A friend suggested I should use Dewey decimal system, “there was no going past it!”, but straight away I knew it would not be useful. For a start all the books would have the same basic number because they all belong to the same ‘subject’ area, or do they? Yes, they belong in a same or similar artistic genres but the actual subject matter of the books varies enormously. As far as I have had contact with the Dewey system, and probably this is also true of all the alternative systems,2 it is about shelving; all the books on the same subject or by the same author sit together on the same shelf, but it was really obvious from the start that this was not going to be possible. I have since found out that the Dewey system is far from perfect and has significant biases and lacunas. I know of one collection of books by artists in a university library which remains uncatalogued because the system can’t fit them and the librarians don’t have the time to deal with the problem. So, perhaps naively, I thought up my own system based around what information I thought would be important to record about the book.

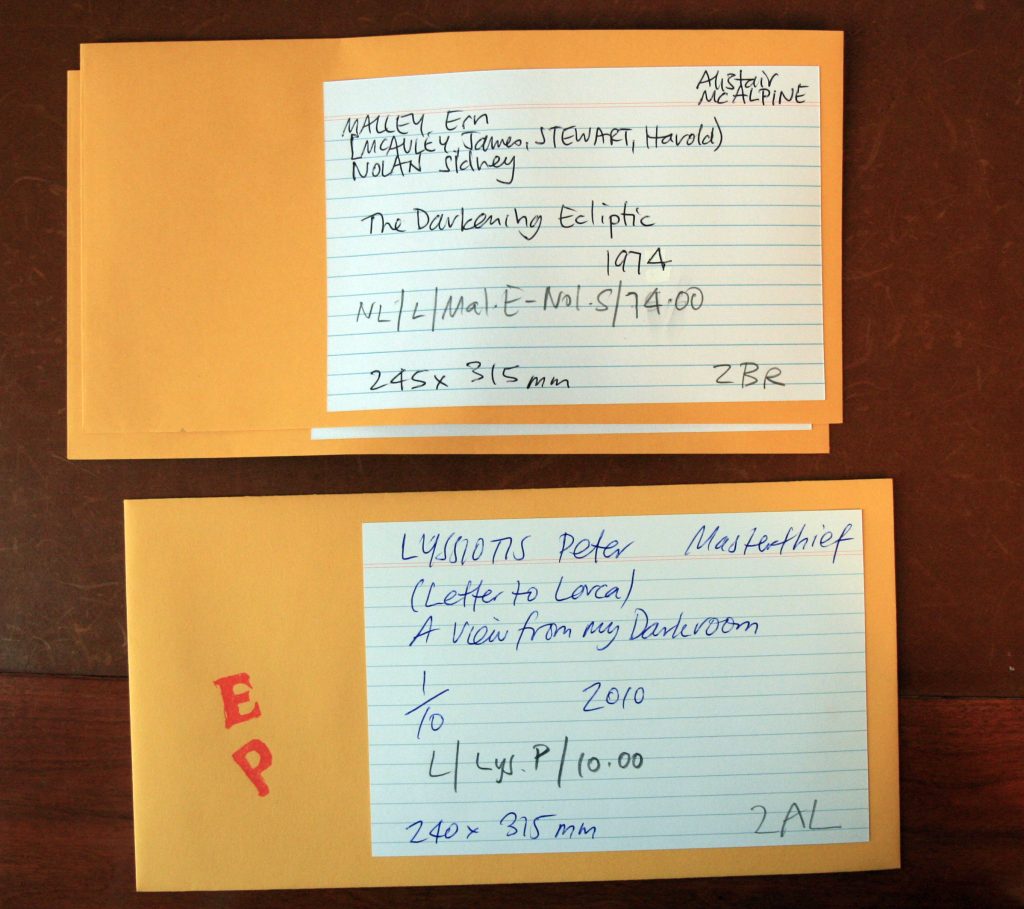

Recorded on the card are the makers of the book, the title of the book, the publisher if there is one, either the name of the artist’s ‘press’ or perhaps a commercial publisher, the edition number if there is one, the date of publication, the dimensions of the book and the place marker, i.e. in which cabinet the book is shelved.

Initially, the catalogue was split, and the cards were kept in separate boxes. The books were divided between limited editions and non-limited or open editions. I marked books as limited only if the book was numbered—edition of 10, copy number 1, for example. I thought this split would mark a difference in production aesthetic, that the ‘limited editions’ would be small press, hand made books, limited because of the high labour input required, and ‘open editions’ would be more commercially produced books, small offset or photocopied, but then I bought some photocopied zines and noticed when I was cataloguing them that they were signed as limited editions. Also I had hand made books that I knew were limited editions, perhaps 6 copies in total. I knew a second edition could not easily be produced because of the production method, the artist had made small batches of paper specifically for the project, but the books were not numbered or ‘declared’ to be limited.

The significance of the ‘limited edition’ is that even if the book were a sell-out success (wouldn’t that be nice!) the maker/publisher would not then go and print another edition, unlike an open edition where the maker/publisher could keep printing new editions as long as the book was selling.

So the catalogue was recombined and re-split. All the bookworks are together though the L indicating the limited edition and the NL indicating Not Limited is still maintained in the reference numbers. Reference books (R) have been separated into their own catalogue box and onto their own set of shelves. Other notated catalogue letters and abbreviations are: H = historical, F = facsimile, Anth = anthology, C = catalogue, M = magazine or journal, P = proof, B = broadsheet.

The next key information in the reference number:

the maker/s name/s abbreviated usually to the first 3 letters of the surname plus an initial. All the makers are recorded in the reference number.

the year of production

the number of the book made in that year

With the reference books, usually small catalogues, that state no author or curator they are recorded under to their country of origin, or their publisher.

Recording the position of a book has become crucial. Each cabinet is numbered, currently 1 – 4, each shelf lettered, A, B, C, etc., and most shelves are split left and right. So a book can have a place marker 3BL. If there is a book hell in the arena of collecting, it is losing a book. It is not the big books that are at risk of disappearing but the small ones.

The catalogue card is glued to an envelope. The envelope is there to contain additional information about the book if I have it, or correspondence from the artist. I’m always in the process of looking for information, asking the artists to send me an artist’s statement or extracting statements from exhibition catalogues or surfing the internet for extra information about the book itself or the artist who made it.

I have, over the years, wondered how useful my catalogue is. At its most basic it is a list of the books. It is also a tracking system and gathering point for information about the book. Now with such a large number of books catalogued, the hardest thing is realising that I should have included specific data that I didn’t think to include when I started. Recently a friend asked me when did a get a particular book and where? Accession data! I haven’t recorded that. Well, I do have the data because for the majority of the books I have an invoice…a project for the future!

The website

Once the card for a book has been written and the book has been photographed, it can be entered on the website. My decision to open the collection to the public required a website. Aside from being a digital database, the website is the public’s primary entrance to the collection. Every book is listed and has at least one reference image. So it is possible to view the collection online, or make an appointment, or if you have work you would like me to consider for collection you can contact me.

My name is not on the website so a website visitor does not know whom the collection belongs to. This was a conscious decision, not an omission. I want to maintain a bit of distance, to hold the public at bay, which might sound a bit odd but I don’t want tourists, accidental or otherwise! I want visitors who are more serious about their investigation of this particular genre of books.

The website exists on two levels. Behind the public site is the administration site. I spend way more time on the administration site than the public site. Since the site was first designed in 2006 I have done one major overhaul. This was because the initial design was based around the original categories of limited edition, open edition and reference books which, as the collection grew, proved to be inadequate divisions. Also, feedback from visitors indicated they hadn’t actually looked at the website at any depth.

For the new version of the website I created a list of 28 categories for the bookworks and 6 for reference books. Every bookwork is assigned at least one category and preferably 3-4. This assignment of categories links books on multiple levels and it is possible to search the collection through the categories. If you select a category and then see the work of a particular artist you want to check out it is possible to move to a listing of their work. The categories also restrict the number of works and images that have to be loaded at any one time. The books are also split into historical and contemporary works. 1960 is the date of changeover. Why 1960? because it was in the 1960s that there was a new surge of artists interested using the book as a platform for their work, so this seemed like a right date to choose.

So the collection has moved far beyond my own work. The core of the collection remains Australian work. But it was important to me to tap into what is being made elsewhere, to take in a bigger picture. When I’d become familiar with what has happening here, I looked beyond to the overwhelming international and historical mass of work. Considering the production of work, those books already made and being made, the numbers are huge. It is a bit like an Aladdin’s cave and a bottomless pit. However the strength of the collection comes as much from what I choose not to buy as from what I decide I must buy. Always my core interest is specifically the book. Always I ask the question, do I want this book in my collection?

- Jack Ginsberg, South African book collector, personal comment.

- Many libraries have their own system of cataloguing, the Stiftsbibliothek in St Gallen, CH, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, UK or the Library of Congress in Washington D.C., USA. (Maggie Patton, curator and librarian at the SLNSW, said they no longer used Dewey at the SL. She also named my cataloguing system as a “fixed location system”.)