What is the difference between a work of art and a work of craft? Are artworks essentially useless, ‘decorative’ objects while craft-works are useful, functional objects? Does this mean the book has always straddled the fault line between craft and art?

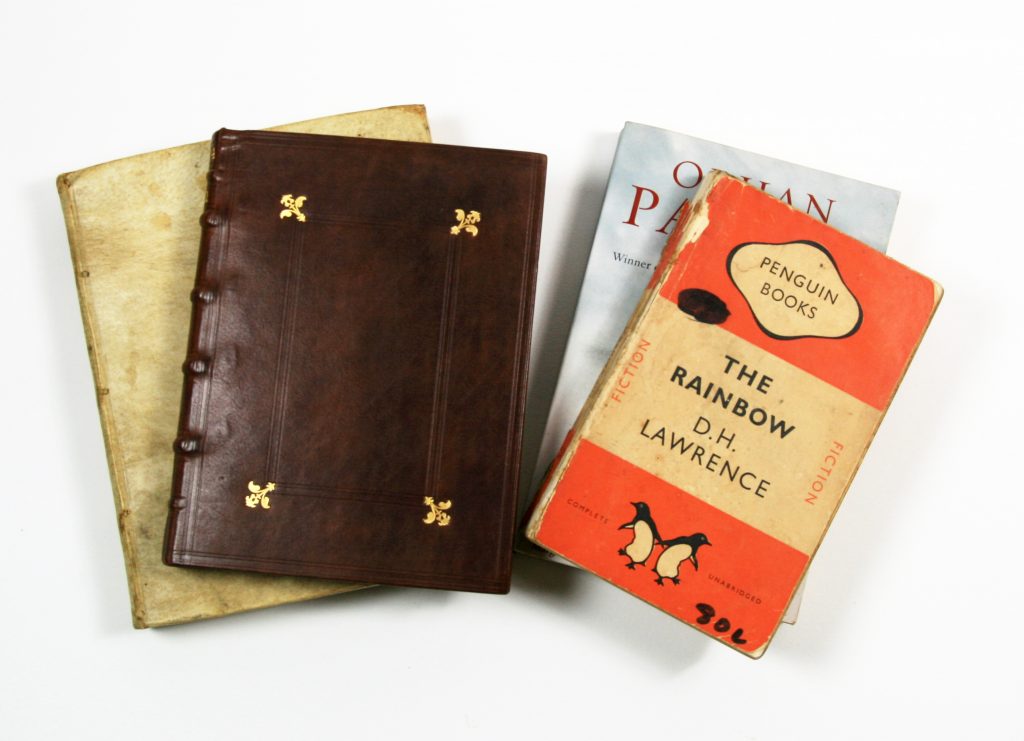

Considering the hand written and illustrated books of the medieval era one realises, with printing, the book segued into general culture more readily than perhaps any other “artistic” object, becoming mass-produced and everyday. Has the mass-produced book degraded the book as cultural object? Can the mass-produced book move back into the domain of art from general culture?

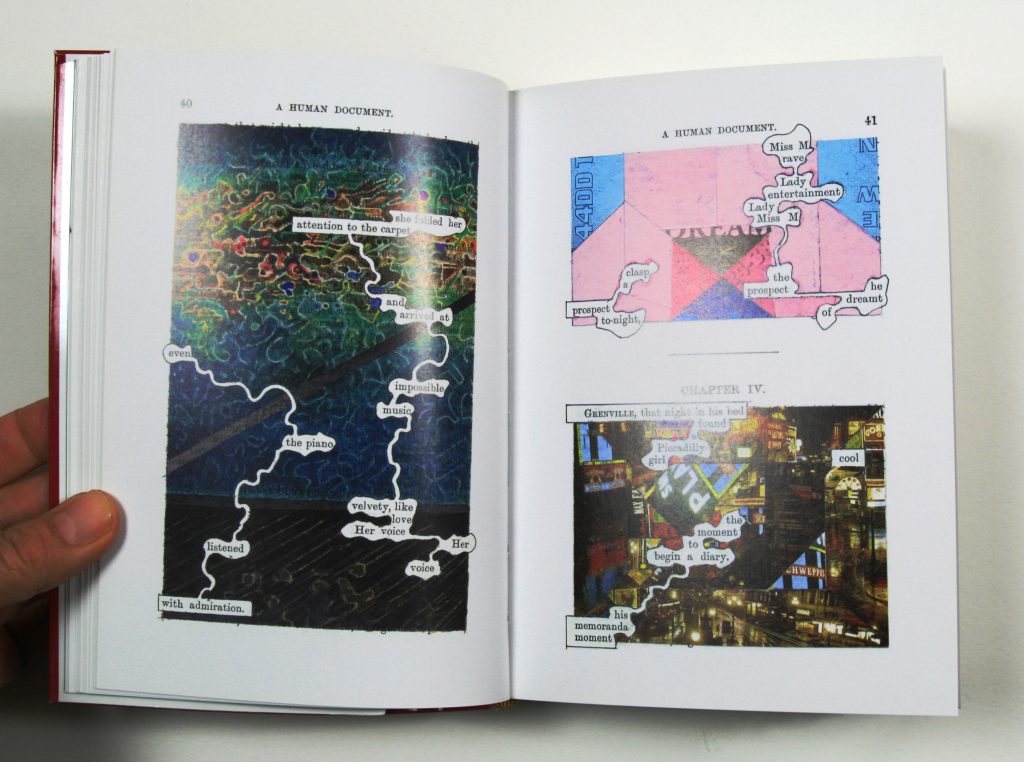

In the 1960s there was a resurgence of artists’ interested in the book. Disillusioned by the commercialisation of the art object and the artist, seeking a new ‘gallery space’, artists chose was the book. It was to be a gallery without walls, and also a portable space. So in an act of defiance, book in hand, they left the gallery and took the art with them.1 The books were not simply catalogues of work which would otherwise be in the gallery on the wall or plinth, they were supposedly artworks in themselves.

To subvert the premium cost factor of the unique artwork, the books were not fine publications but ‘democratic multiples’. The use of the word ‘multiple’ indicated this was not about the unique object. Any element of craft that might have been attributed to a handmade book was also stripped away through the choice of commercial production methods. The word ‘democratic’ captured an enthusiastic belief that this was art for the general public. People would be able to buy art (books) in the supermarket.

Did moving the art, now in a book, out of the gallery, commercialising it in another way, lead to the art retaining its status as art and/or the “common” book gaining a new status as art?

Lucy Lippard writes: “Accessibility and some sort of function were an assumed part of their raison d’étre. Still, despite sincere avowals of populist intent, there was little understanding of the fact that the accessibility of the cheap, portable form did not carry over to that of the contents… when the book was opened buy a potential buyer from ‘the broader audience’ and she or he was baffled, it went back on the rack.”2

The democratic multiple as an object of mass consumption fizzed. The masses were not so easily convinced. Lippard again: “The fantasy is an artist’s book at every supermarket checkout counter… The reality is that competing with mass culture comes dangerously close to imitating it, and can lead an artist to sacrifice precisely what made him or her choose art in the first place.”3 The failure of the supermarket dream did not mean the end of this form of book production. If the artist’s intention had been purely to make money they would not have become an artist. The appeal of the supermarket dream was more about reaching a broader audience, about communicating, than about financial gain.

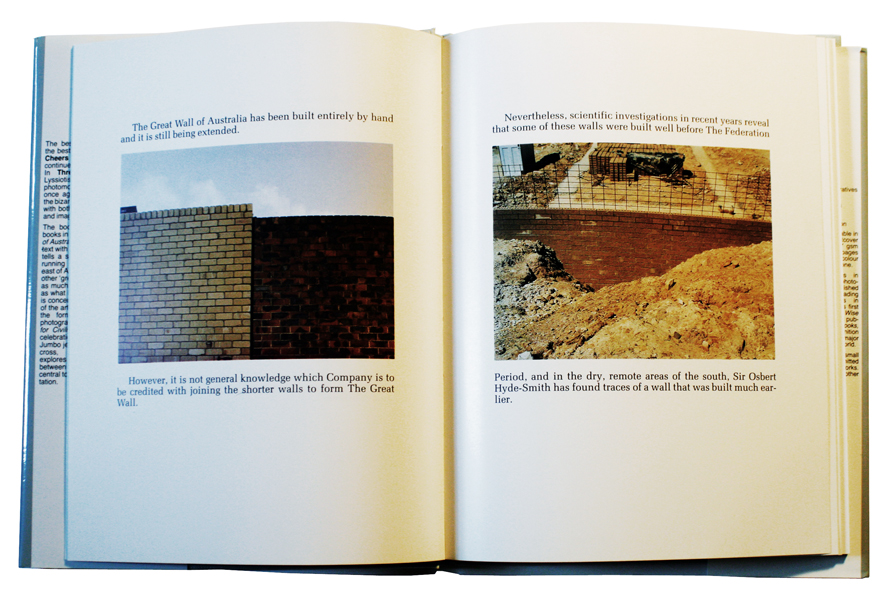

And here the spectre of Marcel Duchamp looms— is it the space that defines the object? Like Duchamps’ Fountain, a so called “ready-made” urinal purchased in a plumbing supplies shop and devoid of all ‘art’ signifiers, could the democratic multiple only be art in the art gallery? Regardless of what art commentators have said and written about the ready-mades, even now the general public would be highly suspicious and dismissive of them. Likewise I suspect the public would still have the same suspicion of these books, democratic multiples, and not categorise them as “art’. They are just books and weird books at that.

Lippard’s comments were written in the early 1980s. Zoom ahead a couple of decades and it is cultural commentary, the writing of (book) art history, that has written the value of these democratic multiples into the art lexicon. The first editions of a select group of these are no longer $5 but $1000+ and definitely no longer for sale in supermarkets! They have become the expensive objects the artists were trying to subvert. The artists, however, are unlikely to be reaping the financial gain. Regardless of the crash and boom, the production of this type of book, with changing print technologies and increased access to these technologies, has not decreased but rather increased and as Tony White points out, the “myth” or “ideal” of the democratic multiple has continued to be sustained.4

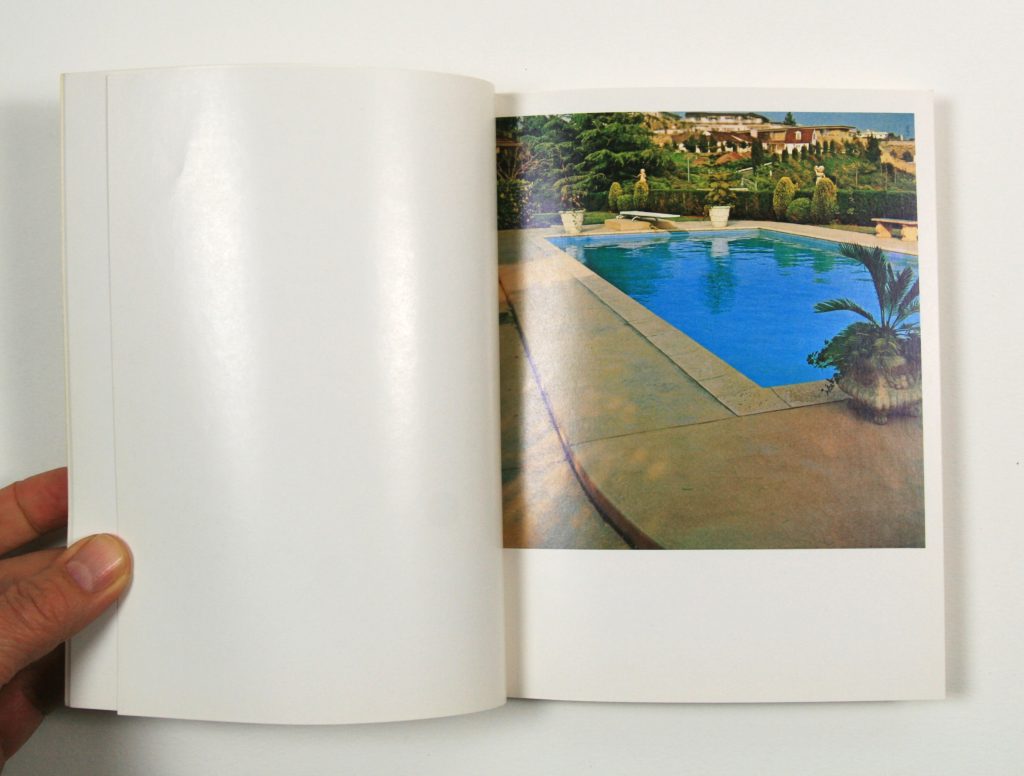

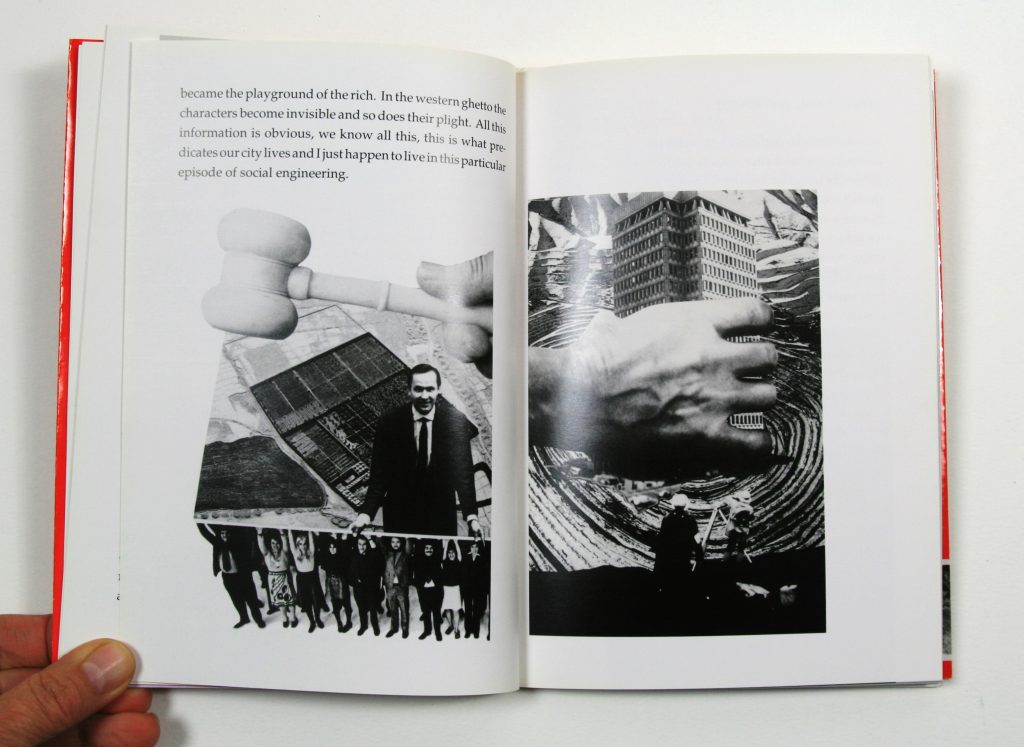

The story so far has been very much USA focused. Taking it in from the cultural periphery, Peter Lyssiotis, Melbourne-based poet, photo-monteur and book artist recalls: “I remember there was an excitement at that time—the cultural centre, the art centre had shifted from Paris (the Old World) to the New York (the New World). And this was caught up in US foreign policy, the rise of America’s clout on all levels. Dropping bombs=dropping democracy! There was a sense of liberation but also there was this dumbing down— Pollock dribbling paint was another. Andy Warhol and his poster works with direct links into advertising and graphic design was an example. It was like the democratisation of the art— anyone can do it! It was a myth but we believed it! We didn’t realise there were strings attached. The same happened with books in some ways. The French, think Vollard, Teriade, Kahnweiler, had offered us the livres d’artistes, high end production, limited edition, expensive books, using the talents of famous artists and poets. The Americans pushed back with Ed Ruscha and the democratic multiple. For us here in Australia these little books were exotic and rare! I have just found out about British Empire rights. Book publishing rights had to be traded between the British and American publishers. These small time artist publications would have been totally off the radar of the publishing industry. Going through normal channels, the books would have had to have been republished by a British publisher to be available in Australia— except, and there is always a chink in the armour, if someone wriggled around the edges, and managed to bring in a small, non-commercial quantity such as the Grove Press, the Black Mountain Writers and City Lights. I don’t know. Bob Gould, activist and bookseller, was the chink. I remember seeing these books. They were like gold. Possibility. I was always disappointed by exhibitions, they were a flash in the pan. Yes, the book was the gallery without walls but also was the exhibition without end date.”5

In Australia the gravitas of the idea was also dissipated by small population and distance. The inter-city communications without the internet were poor.6 I doubt any artist producing this type of democratic multiple ever believed the books would be for sale in Coles or Woolworths. This lack of impetus and broader network has meant that such books have been largely overlooked. The democratic multiple is only one form that an artist’s bookwork can take. In Australia in the 21st century, it is still the type of book that appears least often in exhibitions and competitions. Is it because curators and audiences still do not readily accept them as artworks? Is it because artists themselves still do not readily accept them as artworks?

What makes an object a work of art? Is it simply the medium— that the work is a drawing, a painting, a print or a sculpture? Many would answer yes! the media— paint, pencil, ink, clay, is exactly what makes something a work of art. Even if the work is awful, it is still an artwork! Is art at its core about aesthetics?

What makes an object a work of craft? The making seems to lie at the core, a quality of hand-made-ness, combined with a quality of materials— and its function, that it is a useful thing. In a world full of mass produced machine made objects, “bad” craft works don’t get a look in and “good” craft works become prohibitively expensive, sold in galleries, too expensive to be actually used. Do they therefore drift towards becoming artworks or is craft about workmanship?

Books are not works of art, not necessarily, even those filled with images of artworks. The craft-ness of the book is also not necessarily a concern, though it could be. Neither art-ness nor craft-ness are intrinsic to the book. Does this matter when considering a book by an artist? Are we too caught up in the art of ‘art-ists’ book? We could ask, what carries ideas best? The power of the book still lies deeply in the coherence, depth and expression of the content within and through the object. The book’s position straddling the fault line between art and craft is to its advantage and its disadvantage— is there anything wrong with being the black sheep?

- In “From Democratic Multiple to Artist Publishing: The (R)evolutionary Artist’s Book”, Tony White writes: “One of the myths about artists’ books from the 1960s is that they flourished outside the hegemony of the dominant art world, the art gallery system. From the 1960s through the 1970s the artists with the most notoriety and success at selling these books benefited from their gallery connections and support, not from the lack of them.” (p.45) Art Documentation, Spring 2012, vol.31, No.1

- Lippard, Lucy “Conspicuous Consumption: New Artists’ Books” in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, Ed. Joan Lyons, Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1985, p.50

- ibid

- White, Tony, “From Democratic Multiple to Artist Publishing: The (R)evolutionary Artist’s Book”, Art Documentation, Spring 2012, vol.31, No.1

- Personal correspondence from Peter Lyssiotis

- Through her gallery, Grahame Galleries + Editions, in Brisbane, Qld, with its publishing arm, Numero Uno Publications, Noreen Grahame has been the longest and most committed supporter of this type of bookwork in Australia. https://grahamegalleries.com.au/